It’s wildfire season in 2018. If you don’t live in the western half of the United States (or other areas on fire), this probably doesn’t mean much to you. If you do live in the western United States, this isn’t news to you, and you’re probably sick of the smoke already.

But, to sum it up, “Lots and lots of stuff is either freshly burned, actively on fire, or likely to burn in the very near future.” Forests, grasslands, and, sadly, a lot of structures.

Why am I writing about this? I live in the western United States, have been under varying levels of smoke for quite a while now (this is normal in the late summer), and have recently been doing a lot of reading on US wildfires, and there are some interesting things that fall out of that!

Wildfires and Smokey Bear

“Only you can prevent forest fires!” If you’ve spent any time in national forests, you’ve seen or heard this phrase - with the bear in the hat right there as well. It’s certainly worth keeping in mind that you should be careful, but in the United States, many of the large fires are caused by lightning storms. Human caused fires tend to be caused around where humans are, so they are frequently caught earlier. Storm caused fires often start out in inconvenient places, far away from civilization, where it’s hard to get fire crews and harder to spot the fire in the first place. Although, we’re seeing more “human caused” fires starting out in inaccessible places, and evidence would seem to indicate that some power companies could be doing a better job of line maintenance.

Whatever the cause that starts them, wildfires can grow incredibly rapidly, move frighteningly fast, and cause massive damage. But, they’re also needed to clear undergrowth, release certain types of seed pods, and are a natural part of western forest lifecycles. They’re not that large a problem if they’re contained to the ground, but recently, one might get the impression that forest fires have learned to climb. Most of the massive fires we see are crown fires - where the whole tree is on fire, instead of just the brush along the ground. Those are massively more powerful, and a good bit more destructive (to forests as well as structures).

We’ve also seen, more and more, wildfires that threaten (or simply destroy) structures. Any large fire will be followed by aerial shots of neighborhoods that are just flattened. There’s nothing left standing. It seems like a huge wave of fire has gone through and demolished everything, though, as I’ll cover later, that’s not exactly the case - and I’ll teach you how to recognize what’s gone on.

Wildfire Fire Management in the United States

Wildfires have been part of the western United States since long before the lands were part of the United States, but things really started to hit the public awareness with the Great Fire of 1910. This fire burned 3,000,000 acres mostly in Idaho & Montana, and was a combination of a bunch of other wildfires that had already been burning, which merged together when weather conditions caused incredibly strong winds. Several days later, enough rain showed up to put the fire out. It went through and leveled quite a few towns, and did serious damage to plenty of other towns.

|

| Wallace, Idaho: By National Photo Company - U.S. Library of Congress |

One of the firefighters on this fire, Ferdinand A. Silcox, who became the Chief of the Forest Service in 1933. He proceeded to put the “10 A.M.” policy into effect - that all wildfires should be extinguished by 10 in the following morning, or if that’s not possible, as soon as possible after they start.

By the late 1940s, the Forest Service had the equipment (Jeeps, aircraft, etc) to actually be able to do this reliably - and, for quite a while, it worked very, very well! Forest fires were stopped early, contained, and did relatively little damage for quite a few decades.

Unfortunately, this tactic was one of “those things that can’t go on forever” - and if something can’t go on forever, it won’t. What this missed was the role of fire in clearing out low growth, killing weak trees, and generally helping maintain a clean and viable forest environment.

In the early 1960s, Dr. Richard Hartesveldt began experimenting with giant sequoias, and realized that their seeds only germinated after a fire. The trees hadn’t been able to germinate any new seedlings in areas that weren’t allowed to burn, and this raised questions about the overall “Don’t let it burn” policies in place. Not much came of this, though, and the Forest Service continued putting out fires as fast as they could find them.

Fast forward a few decades, and by the 1990s, it was becoming increasingly obvious that things just weren’t working. Fires were getting larger, and the 1988 fire season was fresh in people’s minds (burning over 700,000 acres in Yellowstone alone). Unfortunately, nearly 50 years of forest fuel buildup were still on the ground, and the United States has a lot of forest out west. Until the debris cleared out, things were just going to keep getting worse.

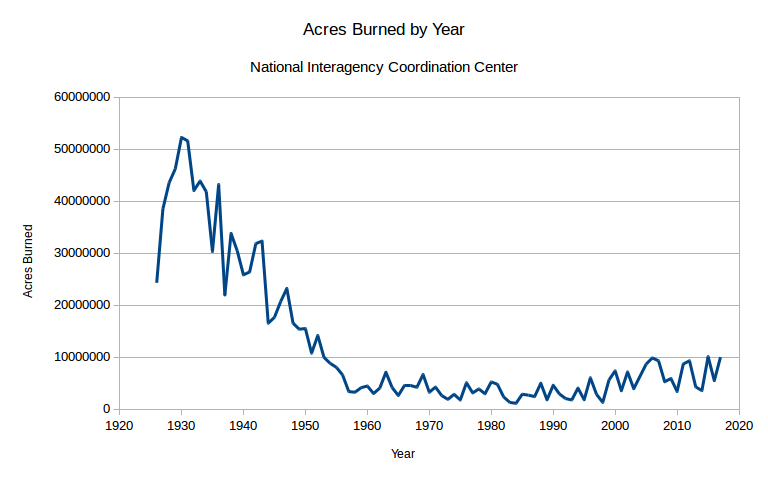

And they have. The National Interagency Fire Center has data on wildfire acres burned, and while the old data isn’t nearly as good as the new data, the general trend is clear. Starting in the 1930s, the acres burned plummeted - and remained low until the 1990s, at which point things have started to tick up again. There are a variety of causes, and the warmer, dryer weather we’ve had certainly isn’t helping things, but fundamentally, suppressing forest fires is just kicking the can. We’ve kicked that can for decades, and we’re running out of road.

Another factor is that more and more homes are built in the wildland-urban interface zone - or, more simply, “In the forests that like to burn.” In the western, wildfire prone states, the number of homes at risk from wildfires has increased from 600,000 to 6.7 million since the 1940s. And, certainly, this is a result of increasing populations, but density of structures is a serious problem for wildfire destruction.

Forest thinning efforts exist, and certainly help in interface zones, but there’s just too much area to reasonably thin mechanically. We might consider allowing a bit more logging in the forests, though. Modern logging is far beyond what people think of from Fern Gully or Captain Planet. We’ve learned a lot, and thinning a forest can help reduce the intensity of fires, or help reduce the rate of spread. A policy of “Don’t log it, don’t let it burn,” though, simply doesn’t work indefinitely. And we’ve reached the edge.

Home and Structure Ignition from Wildfires

The news loves showing pictures of former neighborhoods, flattened by fire. You see them after almost every single wildfire that’s gotten into an urban interface zone. You’ll notice that it’s rare to see one home burned - you see entire neighborhoods, burned to the foundation. Why? And how can we prevent this?

The general understanding of this type of destruction is that some huge, evil flame monster just went rampaging through the neighborhood, incinerating everything in sight all at once in a towering inferno of flames, and there was nothing anyone could do about it.

There’s only one problem with that: It’s entirely wrong. Starting in the 1990s, researchers began really diving into the timing of urban fires in the interface region, and what they found was that fires in developments typically started half an hour to an hour before the main fire front actually arrived, and continued for 4-8 hours afterwards. In this particular aerial shot, a house is fully engulfed, 7 hours after the fire went through. It’s not a wave of flame - it’s house to house spread, starting early, and continuing on for a long period of time after the fire has gone through.

Take another look at the photos above, and you’ll notice something else: The vegetation around houses is still mostly intact. Some trees are burned, certainly, but many of them are still standing - and clearly not burned. A wave of flame passing through would ignite the majority of those, but the only ones you see damaged in a destroyed neighborhood are the ones that have been ignited or charred by a house burning nearby.

Other photos of the destruction show something else: Houses burned in wildfires almost always burn from the top down. Take a look at the house on the right - it’s clearly burned out, but the structure is still intact. The roof caught fire, and it burned down. You’ll spot this in many pictures of neighborhoods on fire - the top half of houses burning while the lower half is intact. This picture is another example of “perfectly intact landscaping around burned out houses” as well.

If it’s not a wall of flame igniting houses, then what causes whole neighborhoods to burn down?

Firebrands.

Firebrands are simply sticks, twigs, leaves, house parts, and other material that gets lobbed ahead (or behind) a fire, actively on fire, and lands on or around a house. Typically, this lands on the roof, catching the roof on fire (debris buildup is a major contributor to this sort of ignition), and then the house burns down.

They can also ignite something around the house, that then burns up against the house, also setting the house on fire.

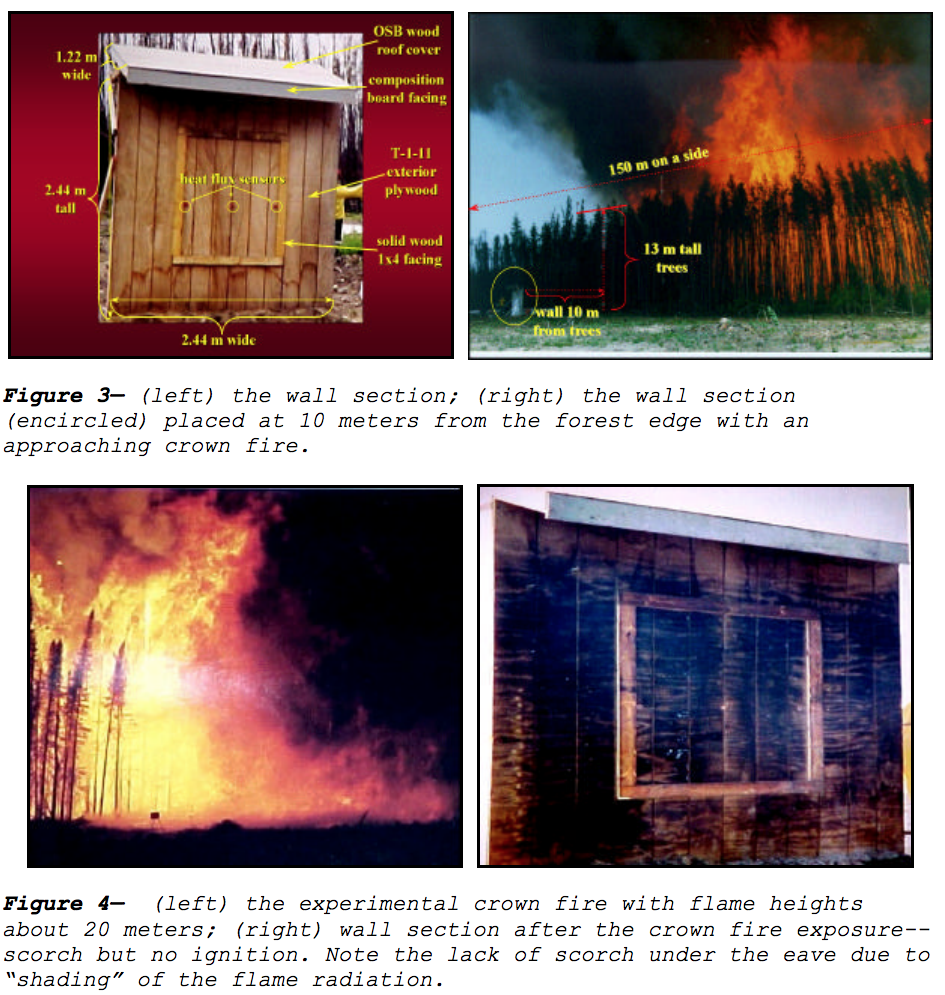

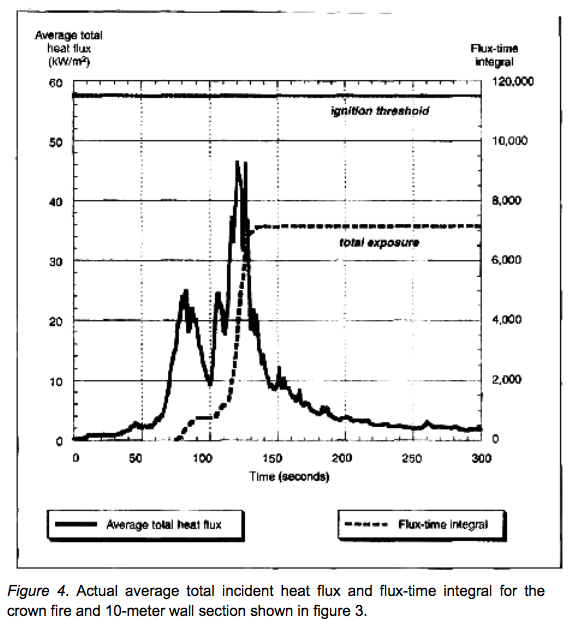

The radiant heat of a burning crown fire can ignite a house, but it has to be extremely close. Houses just don’t catch fire from short bursts of radiant heat, even radiant heat that radically exceeds the pain threshold for humans. Something that will give a human severe burns in seconds will take minutes to light an exterior wall on fire.

Jack Cohen’s Research

Much of this research came from Jack Cohen. In the late 80s, he began looking into how, when, and why structures burned from wildfires - and realized that the type of roof on a house made a huge impact in whether it survived. Wooden shingles almost guaranteed that a house would be a smoking heap of ash, while more fire resistant and fireproof roofing improved the survival odds greatly.

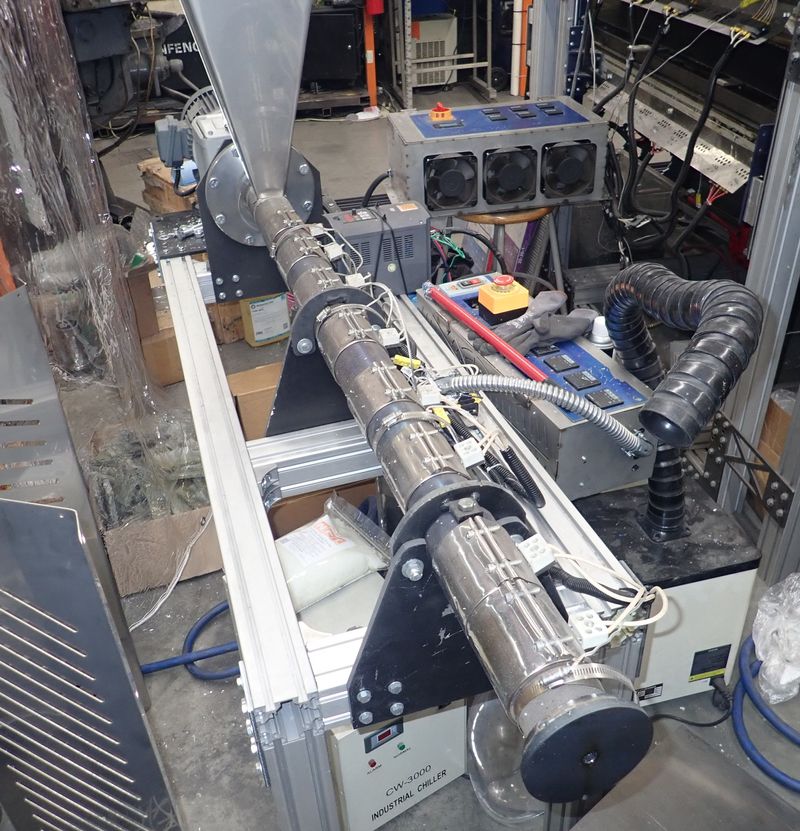

After realizing that many of the forest fire propagation models created results that simply didn’t match reality, he began doing more experimentation, which included live, instrumented burns of sections of forest.

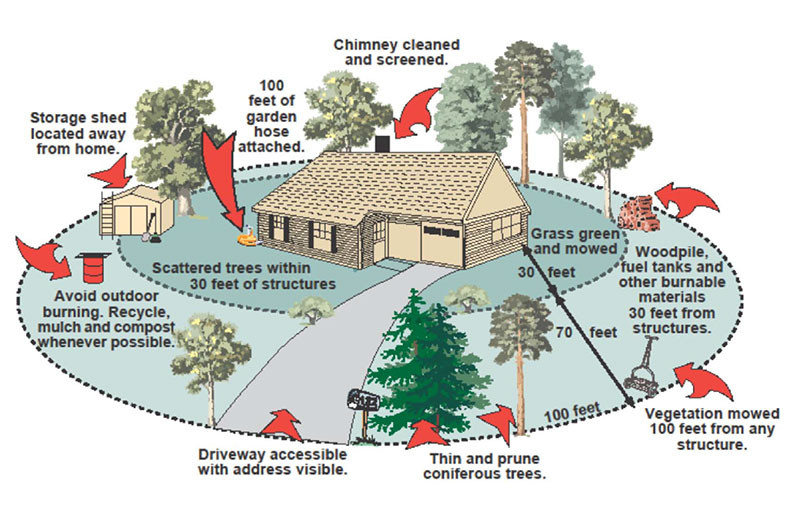

And this research led him to the conclusions that, for the purposes of structure survival, the only things that matter are the house, and the 100’ or so around the house.

His groundbreaking research didn’t exactly change the world in the late 90s when he presented it, but it’s out there - and you can read it yourself. Or related articles. He did a lot of writing, and he had the data to back his claims up. It’s hard to beat real world tests - here, the wall above, got more than hot enough that you wouldn’t want to touch it (and withstood heat fluxes that would sizzle a human in a second), but it didn’t catch fire.

Outside about 30m/100’ from the house, even a raging crown fire (or house fire) simply doesn’t deliver enough radiant heat flux, for long enough, to light a typical house on fire. The ignition has to come through other means. That can be flame spread across the ground, or, most commonly, firebrands.

But it’s far, far easier to defend against those than it is to defend against radiant heat. Old suggestions, assuming radiant heat as the dominant ignition source, would suggest that you’d have to clear hundreds of feet around a house, and have it be barren wasteland, to avoid ignition. Not only is that incorrect, if you don’t address the roof and house construction, the house will still probably catch fire. Firebrands can start fires half a mile beyond the flame front, and in some cases have been seen over 10 miles ahead of the main fire!

Fire-Resistant Construction and Landscaping

If what’s around the house matters most to wildfire survival, how should you build?

There are lots of guides, both for how you build and how you landscape, but one of the best resources out there is firewise.org - a great collection of material on wildfires and home survivability. The Builder’s Wildfire Mitigation Guide is another great resource. The key is understanding the HIZ - the Home Ignition Zone. Anything outside that zone is unlikely to set your house on fire, no matter what it does. Anything inside that zone? You’d better pay attention to it.

One important thing to note here: If the zones overlap with someone else’s zones, you don’t have separate zones. You have one big zone. In many of the burned out neighborhoods, once a house caught fire for whatever reason, other homes were close enough that radiant heat could spread the fire, or the fire could crawl across the ground, or various bits of flaming debris could ignite the homes next door. For many of the neighborhoods you see entirely flattened, the whole neighborhood counts as the HIZ. If one house lights, without intervention, all the rest will go as well, and this is what you see. Just a chain reaction of house lighting house lighting house, for hours after the fire has passed. Yet another reason to not live within “lean out the window and shake hands” distances of neighbors…

One of the biggest factors in home construction is how the roof is constructed. There are varying degrees of fire resistant roofs (Class A, B, and C), but a lot of roofs aren’t rated, which means they can’t even withstand a Class C test brand.

How big are these test brands? The “A” brand, on the right, is three layers, 12” x 12”, and a whopping 4.4lb of wood. They put this on a roof, light it, point a fan at it, and see if the fire penetrates the roofing structure. If yes, it’s not Class A rated. If it survives this giant hunk of flaming wood, congratulations, you’re Class A fireproof!

Roofing materials don’t always make sense as far as fire resistance goes. Many asphalt shingles are “standalone Class A” - if they’re installed properly, they’re fire resistant. Some metal roofing isn’t - aluminum roofing, in particular, can melt under this test and allow the fire to spread to the underlying structure.

But, at a minimum, you should have a Class A roof in wildfire prone areas.

Beyond that, you should, ideally, have a “simple” roof for fire resistance. This means no complicated interior corners that are hard to seal properly and trap debris (both before and during a fire - though the debris caught during a fire is more properly called “embers”). An eXtension article documents some of the various features in a test house that worked well, or not well at all. A rectangular house with no windows poking out of the roof is ideal here - there’s nothing on the roof to catch debris and hold it, so a Class A roof is likely to hold up very well to burning material landing on it.

Vents are also another big problem. Fire and ember resistant vents exist, but aren’t always installed (or installed properly). If burning material can get into an attic, it’s almost always game over for the house. The design and installation of roof venting is important to how a home deals with a wildfire. One option, popular in manufactured homes, is to simply not have an attic space at all. The roof cavities are stuffed with insulation, and then there’s not much need for venting at all (which means no ember penetration). A tight wire mesh over a vent can help a lot, or you can find vents that are custom designed to inhibit ember penetration. Some of them look a lot like flame arresters. They matter if you’re going to be up against a wildfire!

Consider shutters. They’re classy again, at least if you live near a forest. This probably won’t make a big difference (if the fire is close enough that shutters matter, you’ve probably already lost), but they can’t hurt. Be cautious of vinyl window frames. They melt.

Decks and other attached structures need to be fire resistant, fire proof, or somehow protected. If you’re on city water (or even a good producing well), a low flow sprinkler keeping the deck wet is probably worth setting up. Even if you lose water pressure at some point, a fully saturated deck will be a lot harder to ignite. I might not leave all the hoses on full blast, but a few well placed sprinklers can do an awful lot to help keep things from being on fire. If you’re on a well, there’s a good chance you’ll lose power during a wildfire, but, again, if you keep your flow rate below what your well can supply, it’s worth a shot.

Read up on home and property defense from wildfire. There is, in 2018, a wealth of material on the internet about wildfire safety, structure defense, fire aware landscaping, and it’s mostly backed by data now. Read everything Cohen has published. The man knows his stuff.

Another thing worth considering: The vast, vast majority of wildfire home losses are a very slow process (at first). Some ember lands, catches something small on fire, which catches something else on fire, and eventually the whole house catches. Disrupt any of those stages, and the house will be fine. Most of the neighborhoods that burn are entirely evacuated, so there’s literally nobody left to quench the sparks. Firefighters are unlikely to notice before the house is substantially on fire, so the neighborhood just burns, house by house. If the neighborhood is well prepared (both in terms of construction and maintenance), and there are some people who choose to stick around and deal with the mop-up, quite a few structures are likely to be saved. But, if you do stick around after an evacuation order, you’re on your own. Nobody is coming to save you if you decide this was a bad idea, so you’d better be prepared for pretty much anything nature can throw your way. It’s a decision people have to make for themselves, and there’s a very real chance that if you stick around and things go pear shaped, you die. But, there’s also a very good chance that you can make an impact, not only for your own house, but for the neighborhood (though if houses are super tightly stacked, leaving is probably the right answer).

With wildfires, as with anything, there are absolutely no guarantees. Maybe a tree explodes and lobs a flaming branch straight through a window. But, done right, and with some luck, you can stack the deck in your favor and have a house, standing, after a rather substantial wildfire has gone through.

Grass Fires

Another form of wildfire one might face (and, importantly, the type I face) is a grass fire. These are, on the surface, somewhat less exciting than a forest fire. Flames of a couple feet, tops, moving through dry grass.

And they manage to get people injured quite a bit, since it’s easy to underestimate both their speed and their heat output.

On the plus side (at least for home defense purposes), a grass fire is easier to defend against, because it rarely throws embers, can be slowed substantially by grass cut short, and is generally stopped cold by bare dirt. Those who have followed my recent property improvement posts may have noticed a sudden interest in fire breaks - and this is exactly why. Our hillside is prone to grass fires, and a grass fire isn’t going to cross a large fire break of bare dirt. Since I’ve got an old tractor, cutting firebreaks with a blade is relatively straightforward (at least if you start in the spring when the ground is wet).

My best advice for grass fires? Bare dirt (or gravel) and hoses. It’s not that hard to deflect a grass fire flame front with relatively small amounts of water, and it just doesn’t have the energy to typically cross bare ground. Surround buildings with a few feet of something non-flammable, surround your property with some bare dirt, and you can make very good progress with regards to grass fires. Depending on the wind, you may have to be satisfied with routing it around structures and then letting it burn past.

Mowing your grass regularly is helpful, but may or may not be possible (or useful), depending on the nature of your dirt. If, say, you have a bunch of basalt in a field of cheatgrass, mowing it in the fall is stupid. Mowing it on a spectacularly windy day in the fall is insanely stupid. Just saying. Don’t be stupid with grass in the fall.

If you have a tractor with an underslung exhaust, you might want to consider something else. I’ve changed my tractor’s exhaust from the factory underslung exhaust to an aftermarket stack to avoid starting any grass fires if I happen to be working in grass during the summer. It’s far harder for grass to reach the bottom of this path than the previous underslung path, though it does manage to dump exhaust in my face. An extension may be on order soon…

Final Thoughts

Despite all this, there are no guarantees. Sometimes, things just don’t go well, and despite all preparations, a well prepared and defended house will catch fire.

But you can stack the deck in your favor, and do so in ways that have a significant chance of improving the outcome. By Cohen’s estimates, a house with untreated wood shingles has a roughly zero percent chance of surviving a nearby wildfire. A properly prepared house, with fire aware landscaping, has about a 95% chance - even without anyone nearby to take care of things after the flame front blazes through.

I’m going to go out on a fairly solid limb here and guess that wildfires are going to keep getting worse in the western United States before they start getting better, though eventually the overgrown forests do eventually burn and run out of fuel. But I expect things to keep getting worse, and the hotter, weirder climate we’ve got isn’t going to make things better. Seriously. Everything is on fire.

The good news is that home defense is up to you! While the forests may burn, if you have a properly defended home and landscape, the forests burning literally right to the edge of your defended zone won’t light your house on fire (most of the time). It’s not a government funding problem - it’s a homeowner awareness (and effort) problem. So, get out there, sweep your roof, clear the debris around your house, and keep things tidy. Besides, it looks better!

Book Review: The World Without Us

A popular book from 2007, The World Without Us, by Alan Weisman (Amazon) (eBay, which is far cheaper), talks about what would happen if humans just disappeared from the planet. Weisman looks at the world through this lens, covering all sorts of things - houses, cities, industrial districts, forests, the ocean… all around the world. It’s nicely backed with research and analysis for something that, while unlikely to happen as stated in this book (all humans suddenly disappearing), is happening quite actively around the world as areas are abandoned.

Going forward, if we are at the end of the American Empire, this sort of reclamation by nature will be increasingly evident in regions of the United States as they simply get abandoned. You can see some of it in the abandoned shopping mall photo series that sometimes go around the internet.

This is an absolutely fascinating read, and I enjoyed every page of it!

Comments

Comments are handled on my Discourse forum - you'll need to create an account there to post comments.If you've found this post useful, insightful, or informative, why not support me on Ko-fi? And if you'd like to be notified of new posts (I post every two weeks), you can follow my blog via email! Of course, if you like RSS, I support that too.